The challenge of "Proof"

When I think about the difficulties of teaching now versus when I was a student, the greatest challenge is the availability of information. When I was a child, getting information was the difficult part of school. If I could explain, or demonstrate, or even just retell information, it meant that I had learned the skill of finding information, and processing it. This might take weeks of searching through a card catalog, microfiche, periodicals, and encyclopedias. If information was out there, it was almost assuredly good information because not everyone could become a publisher, editor, content creator (I'm not sure this title even existed then) like they can today. I graduated high school before Google existed, and if you had a burning question you needed answering you either called your smartest friend, or you called Foy Student Union at Auburn University because the folks operating that phone bank were required to give you an answer. I can still remember the sort of jingle we came up with to help us remember the phone number to Foy. It wasn't quite as catchy as Empire, but close.

In the classroom today, none of this is the challenge. Any student can give an answer in seconds to almost any question. They are inundated with information, but the curse that came with this blessing is that everyone can be a publisher, editor, content creator, etc. That sounds great, but now there is no process for vetting and validating what is created. As a science teacher I am accustomed to providing references, and sources that are reliable (Scholarly journals, peer-reviewed articles, etc.) but in the age of constant digital communication, most of those things are lost in the signal/noise ratio.

In order to combat that, teaching students to create and engage in argumentation using the same digital tools that caused the difficulty in discerning valid data. Instead of creating a research paper and submitting it to a scholarly journal which will have an exceedingly limited audience, creating an accessible document with links to the supporting evidence can reach more people, and in a way that they can process. While a reference list in an APA formatted research paper is certainly valuable, in a public sense it won't have "the same effect as clicking on a link to a reputable source..." within the document itself, be that a blog, or social media platform, or other communication tool (Turner & Hicks, 2017, p. 5). This is also the challenge. Because we are writing for a public audience without the structure of an APA or MLA or other such writing framework, all the writing can look similar.

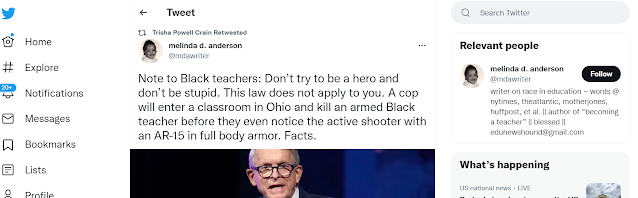

It turns out that integrating what is referred to as multi-modal writing, helps students deepen their skills in creating argumentative writing pieces (Howell et al., 2017). Multi-modal just refers to the incorporation of traditional writing with digital and multimedia tools. While I may personally not like the idea of having to sell information, it is what I am up against in the fight against digital, scientific, and cultural illiteracy as well as intentional misinformation. Digital tools in today's educational world must be utilized to present and support factual, true information, because it is certainly used in the opposite direction. There's one good reason for that, and that is because it works. Using images, multimedia etc. to support or refute a claim is effective and digestible by the intended audience. It does this without seeming like an argument either, and that makes it extra effective (Turner & Hicks, 2017)

If you don't believe this, just think about all the e-mail forwards your parents or weird uncle have sent you that are utter nonsense, but they make bonkers claims in a straightforward way, and combine it with seemingly related images, memes from Facebook, and a link to what they have taken to be a reputable source, even if it has been utterly debunked numerous times. This junk is effective, so we had better get good at combatting it with the true versions of these things.

Howell, E., Butler, T., & Reinking, D. (2017). Integrating multimodal arguments into high school writing instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(2), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296x17700456

Turner, K. H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Argument in the real world: Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts. Heinemann.

We are both "Digital Immigrants" a term coined by Marc Prensky meaning we were not born into the digital age like our student "Digital Natives" (Prensky, 2001, p.1). I think I talked about a similar topic in my blog where I shared my personal experiences from growing up during a pre-"Google" age. While I focused more on the general call for us digital immigrants to employ more technology in the classroom in order to speak the same language as our digital native students, I totally agree that as we teach digital argument skills, we need to also teach our students discernment of what is valid and true among the plethora of information on the internet.

ReplyDeletePrensky, M. (October 2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon 9(5), 1-6.

Turner, K.H. Hicks, T. (2017). Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts: Argument in the real world. Heinemann.

Your blog post makes many great points about the difficulties of teaching digitally. Even though I remember growing up with Google being the main go-to when I needed an answer to a question or when working on a research paper, I used Foy at Auburn to answer many questions as well! I agree with how an issue today is that anyone can go online and be a content creator or an "expert" on something they write about. This made me think of the first example in Chapter 1 of Argument in the Real World, where the author is describing an article written about children vaccinations and the credibility behind the author who wrote the article. Especially since "anyone, anywhere, with access to a smart phone, can mount an argument that can circle the globe in seconds" (Turner & Hicks, 2017, p. 6). It is hard to decipher what is accurate online versus what is false these days, which is why it is even more important we help our students with this and how to form an argument of their own in a digital way.

ReplyDeleteReferences:

Turner, K. H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Argument in the real world: Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts. Heinemann.